THE MILLIONAIRES’ TRIANGLE WALKING TRAIL

Length 1.5 Miles, 30 Minutes

Type: Culture

Difficulty Level: Moderate

Introduction

It is said that by the mid-19th century, Norwich claimed more millionaires per capita than any other city in the United States, with more than fifty residents earning in excess of $1 million per year in today’s dollars. Norwich’s strategic position halfway between Boston and New York made it a desirable location where trade and industry flourished. By the eve of the Civil War, the city was the third largest in the state (after only Hartford and New Haven). Its three rivers—the Yantic, Thames, and Shetucket—powered important industrial mills, such as, the Ponemah textile Mills and the Hopkins & Allen Arms Company, among many other profitable enterprises. The harbor at Chelsea Landing (downtown) was a bustling seaport, a major shipbuilding center, and a hub of wealth, commerce, and influence. Direct access to the Norwich & Worcester Railroad (1840) and a steamship line also put Norwich on the map by providing ready transport of goods and people in and out of town.

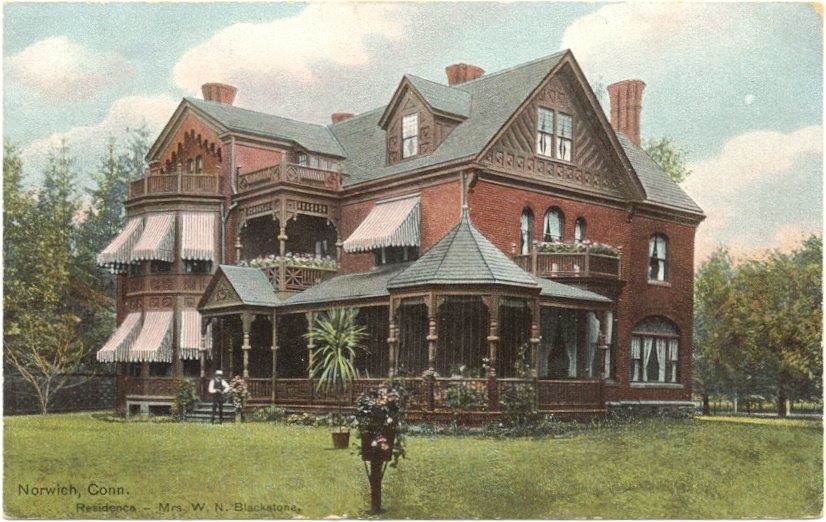

By the early 1800s the Millionaires’ Triangle—bordered by Broadway, Broad Street, and Washington Street—was on the way to becoming the city’s finest residential district. By the Civil War era, ornate mansions and fabulous gardens had made this neighborhood, just up town from the landing, the quintessential embodiment of the Gilded Age, a period synonymous with the opulent lifestyles of the Victorian era’s newly rich. Shipping merchants of the early decades were followed by a steady stream of bankers, financiers, manufacturers, publishers, lawyers, railroad executives, philanthropists, and a U.S. senator and vice president. Among the august citizens who lived here or nearby was First Lady Edith Carow Roosevelt, Pres. Theodore Roosevelt’s second wife, born in 1861 in the home of her grandfather, Gen. Daniel Tyler (130 Washington Street). Connecticut’s Civil War-era governor William Buckingham (307 Main Street) also had strong social and family ties to the Triangle.

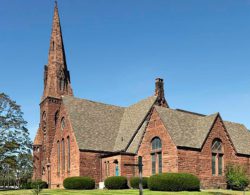

As members of this high society intermarried, they often merged their fortunes, creating even more unimaginable wealth. Yet while they lavished huge sums on their mansions, they also gave back to their community. Their interests in charitable causes illuminate an understanding of important social issues that arose in a tumultuous era marked by the end of slavery and a dramatic rise in immigration rates. Locally, they improved the city’s physical and cultural landscape by sponsoring institutions like Norwich’s Otis Library (1850) and the 1854 Norwich Free Academy (#3) and its Slater Memorial Museum (#3- 1886), along with a splendid new building for the 1874 Park Congregational Church (#22). Norwich’s millionaires also oversaw commissions for some of the city’s most stunning civic and commercial architecture, including the c.1870-73 City Hall (County Courthouse) and the Ponemah Mills in the Taftville section, one of the country’s largest textile production centers when it opened in 1866.

Walk Norwich: The Millionaires’ Triangle Trail is adapted from Norwich in the Gilded Age: The Rose City’s Millionaires’ Triangle, by Patricia Staley (The History Press, 2014). To learn more about the families featured on this trail, please consider purchasing Patricia’s book.

Many portraits of the millionaires from this time period are on display at Slater Memorial Museum.

Parking for the trail is available along Chelsea Parade.